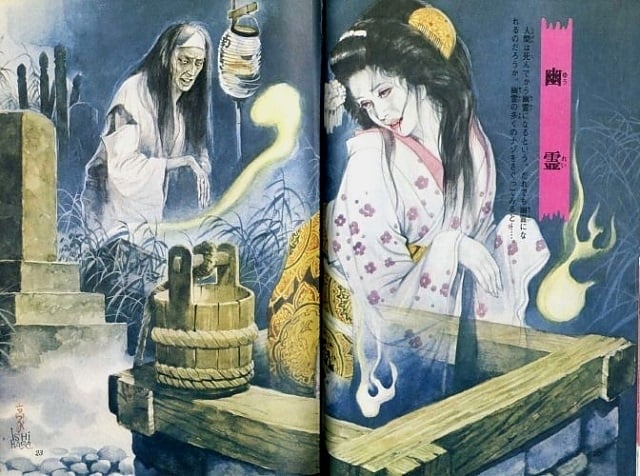

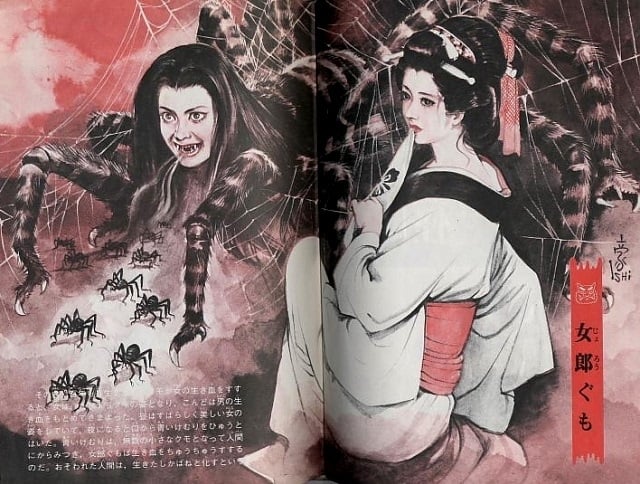

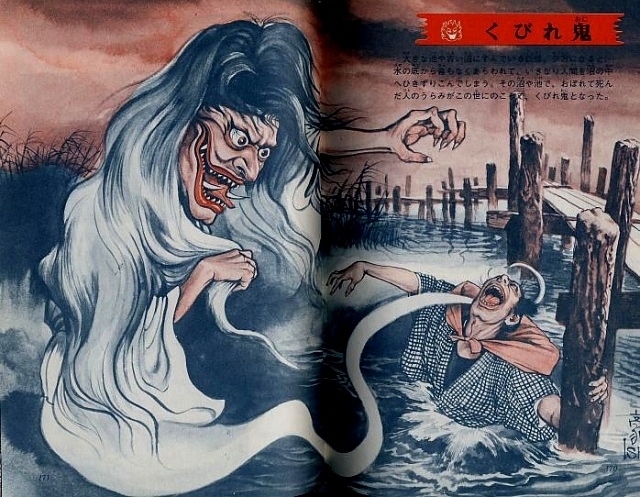

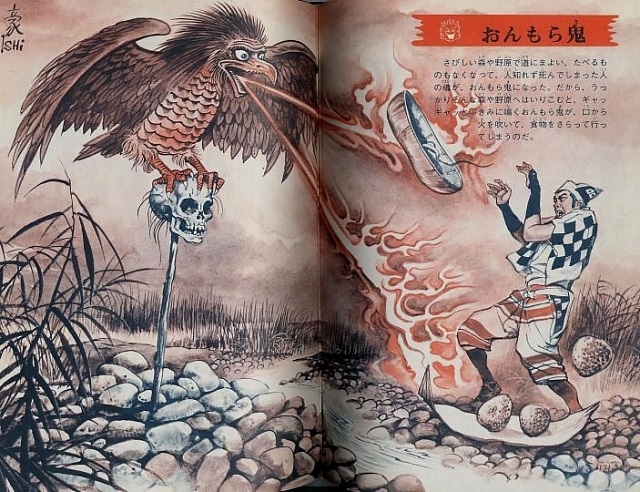

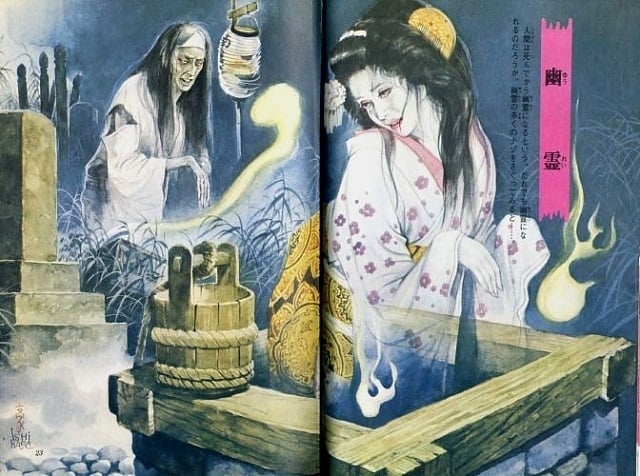

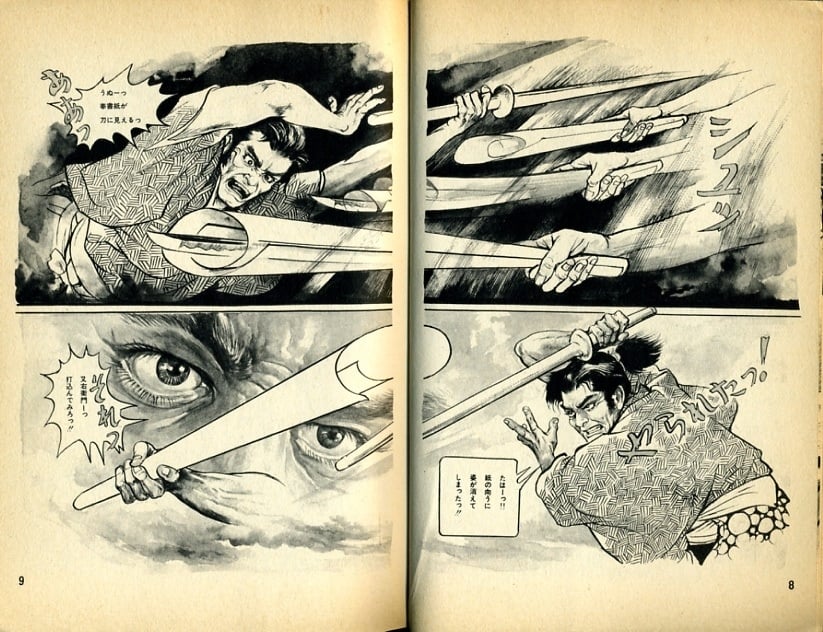

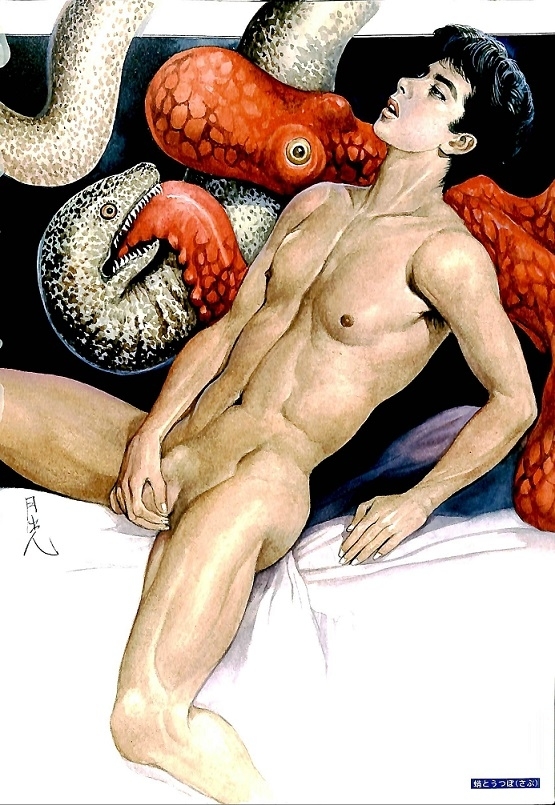

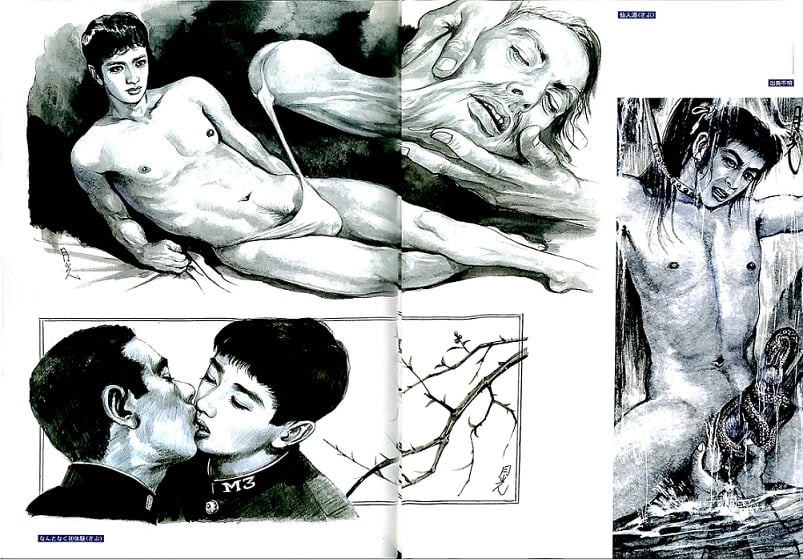

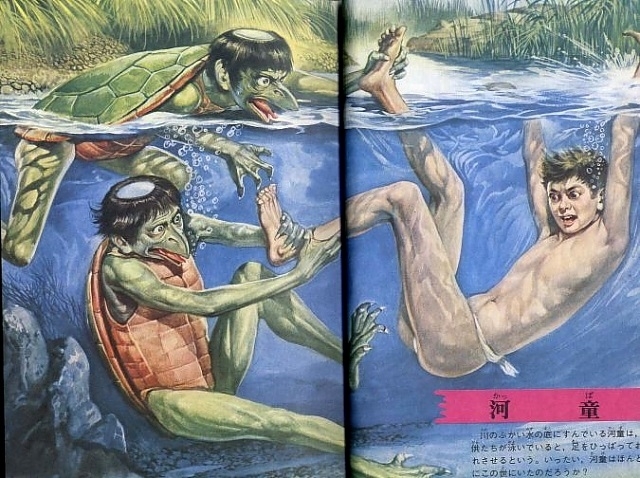

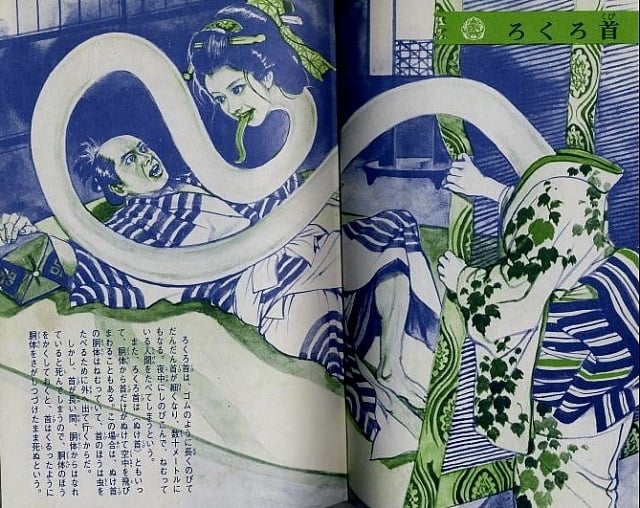

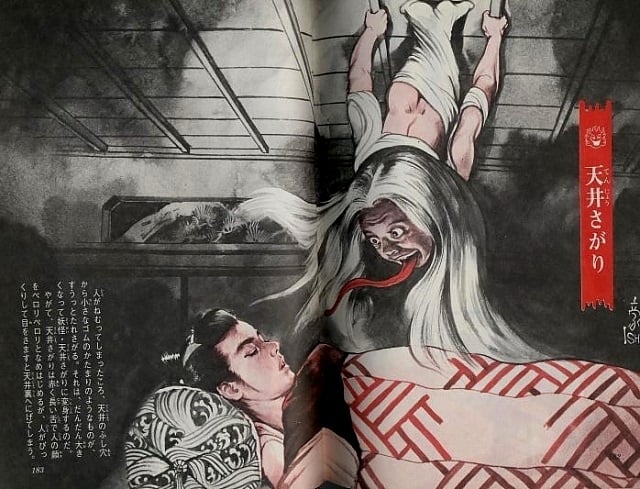

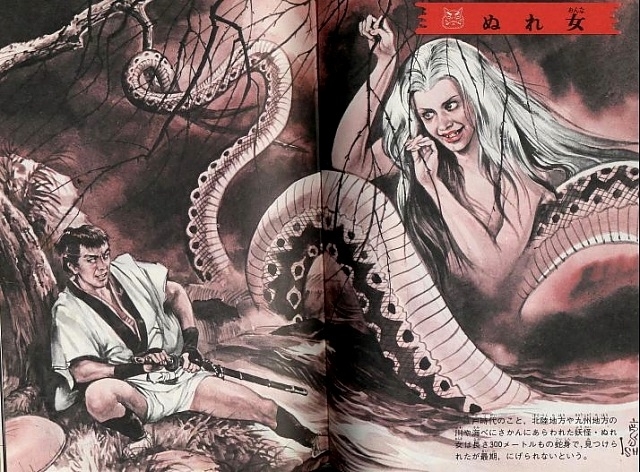

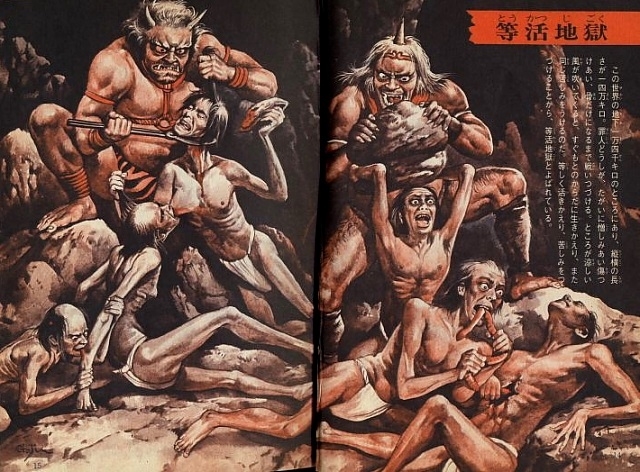

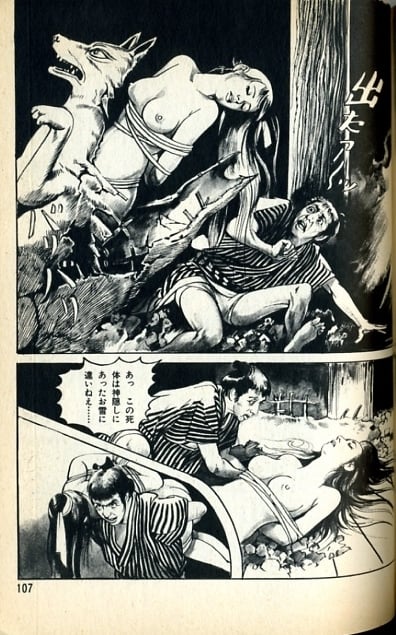

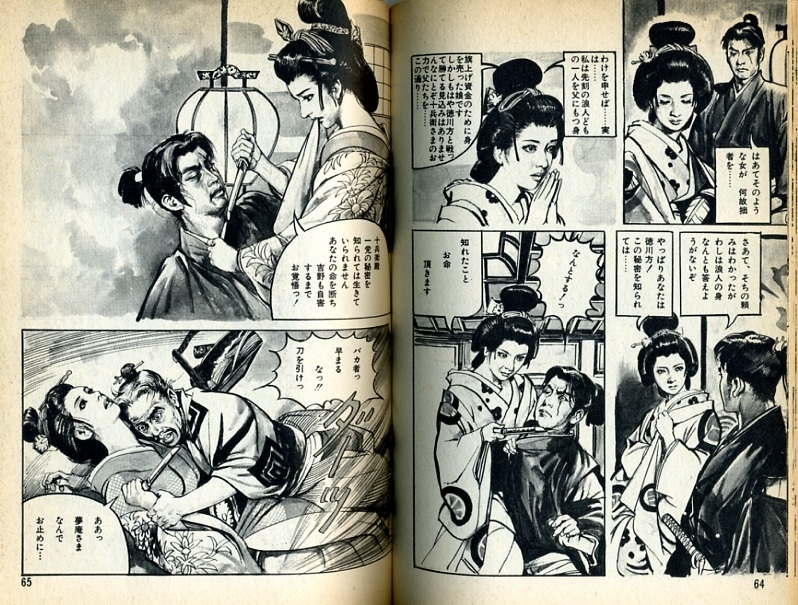

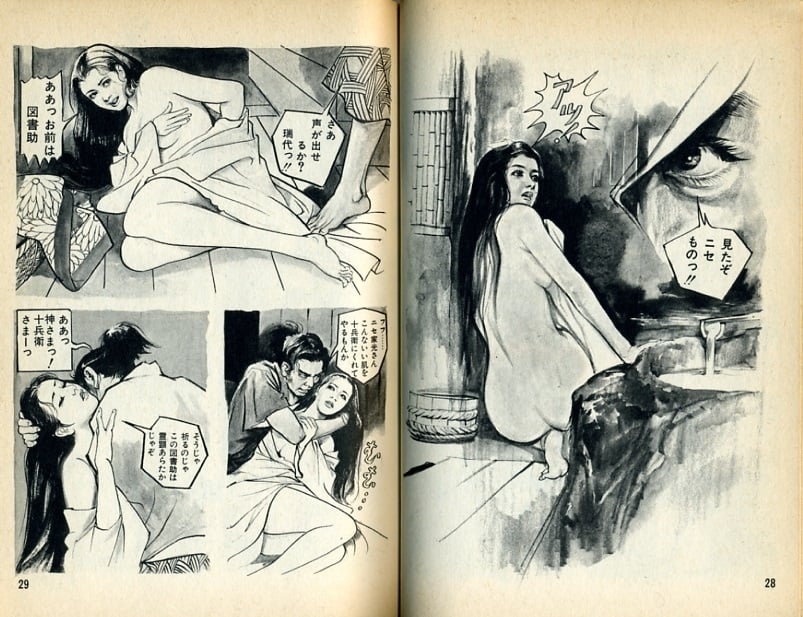

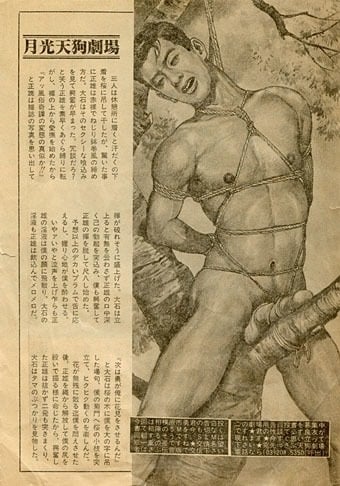

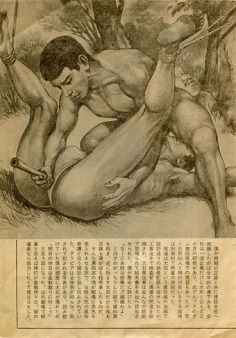

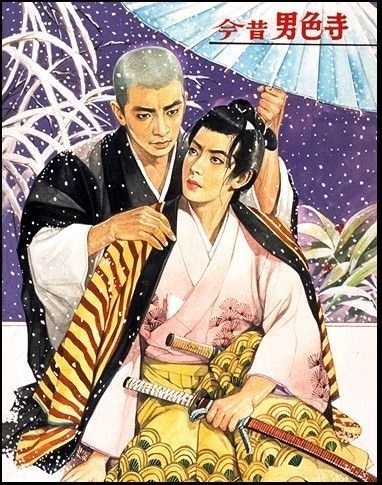

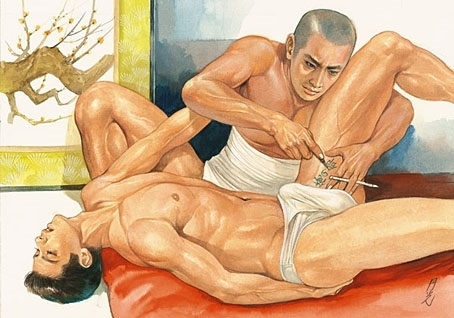

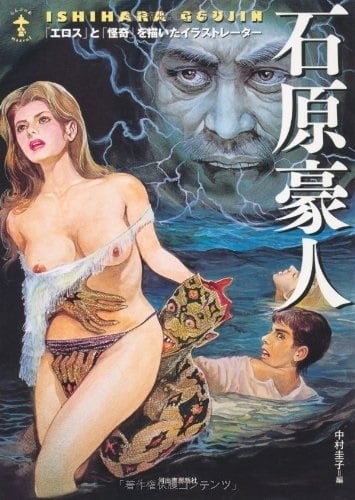

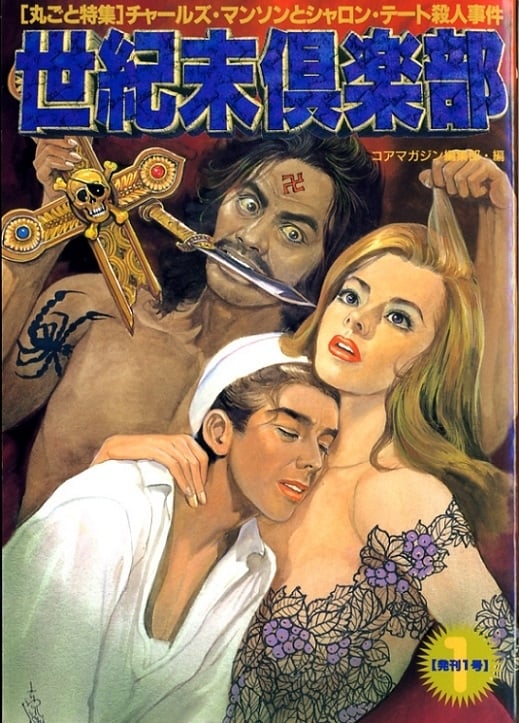

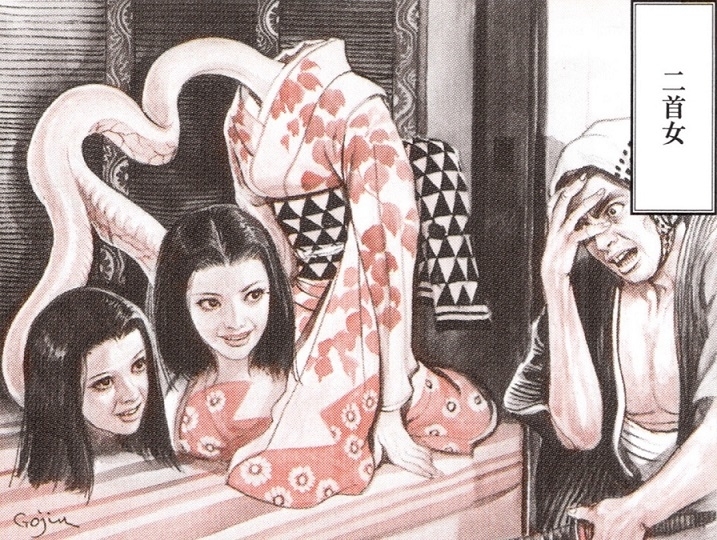

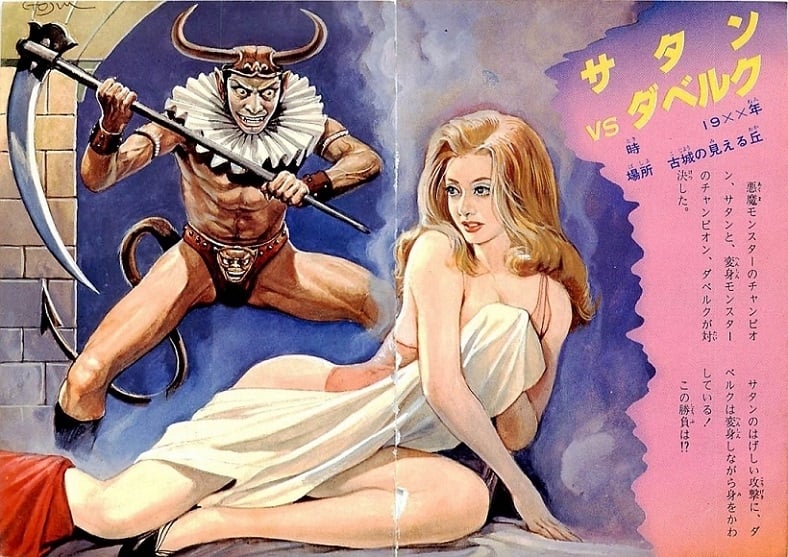

Toru Ishihara (1923-1998), who would later adopt the pseudonyms Gojin Ishihara and Hayashi Gekko, is now known for his illustrations of yokais and monsters for several children’s books, such as “Illustrated Book of Japanese Monsters” (1972) (Fig.1 to 4), for ɱanga, among them Yagyū Jūbē (Fig.5 and 6), published in 1967, whose theme is the love of shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu for the samurai Yagyū Jūbē, and for the numerous illustrations that he created for gay magazines such as “Sabu” and sadomasochistic magazines such as “SM

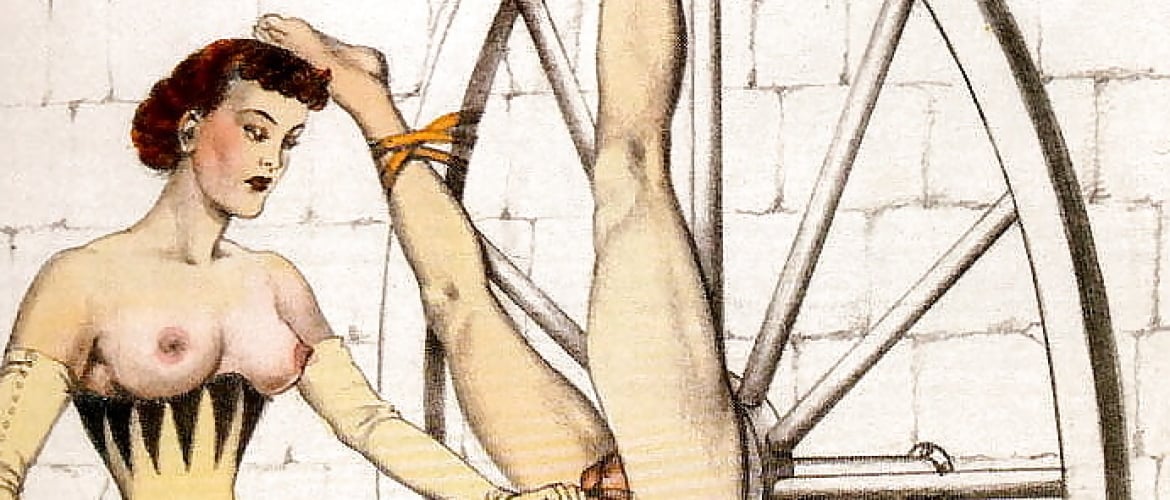

Helpless men chained to various instruments of torture humiliated by bossy mistresses wearing leather boots and intι̇ɱidating outfits. In Bernard Montorgueil’s world it is clear who is calling the shots. But,..

King” and “SM Select” (Fig.7 and 8), already named Hayashi Gekko.

Fig.1.

Fig.2.

Horror Movies

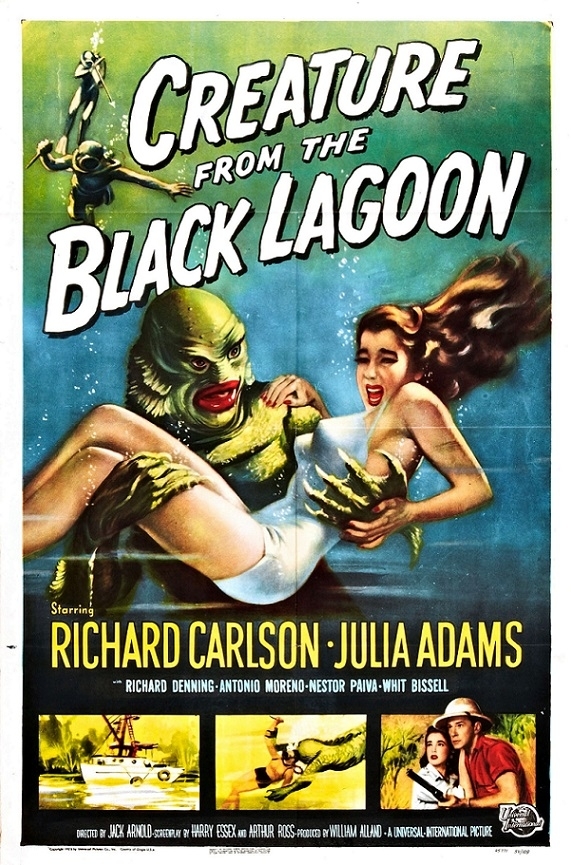

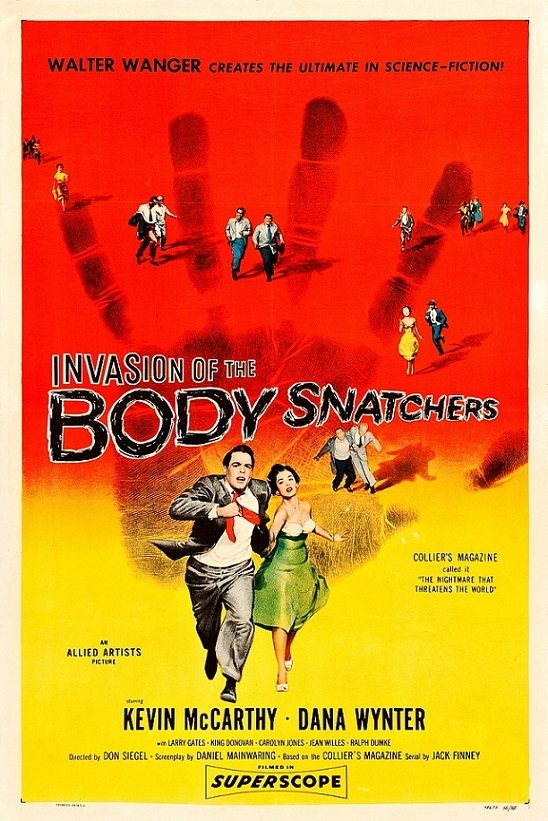

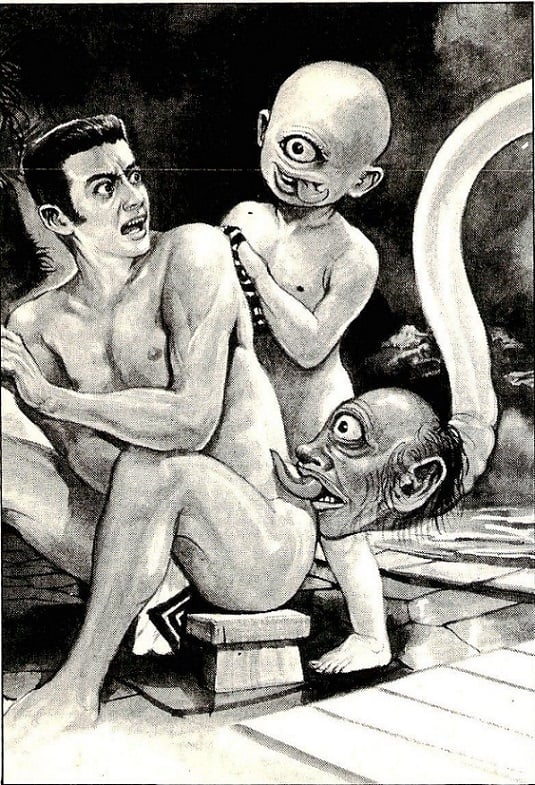

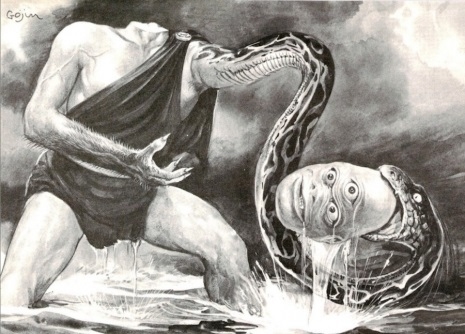

In his illustrations of the yokai, Hayashi Gekko reimagines the supernatural creatures of Japanese folklore in a way quite different from what we perceive in the Edo period´s engravings. In these images, he builds scenes that seem to belong to horror movies from interrupted actions that make the mise en scène become a mixture of dreams and realities with an underlying sexual content (Fig.9 to 16), reminiscent of North American horror and science fiction movie posters from the 1930s to the 1950s (Fig.17 and 18). Such similarity is not gratuitous, as Hayashi Gekko has always maintained a constant relationship with cinema, from his childhood, when he produced cartoons of famous actors, until after World War II, when he painted movie scene cards in Matsue City and produced kamishibai.

Fig.3.

Fig.4.

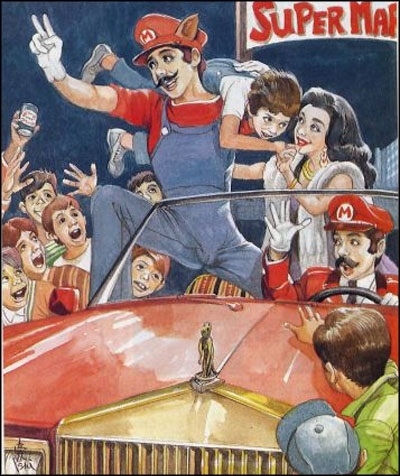

Fight Scenes

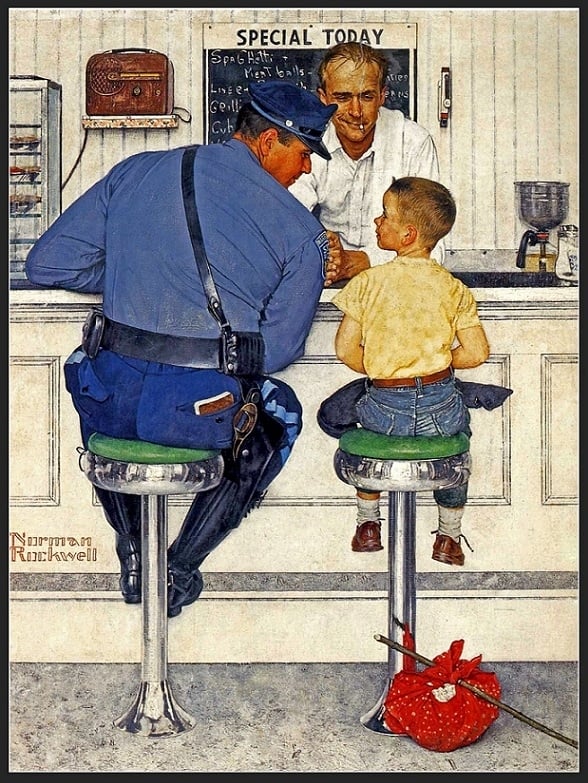

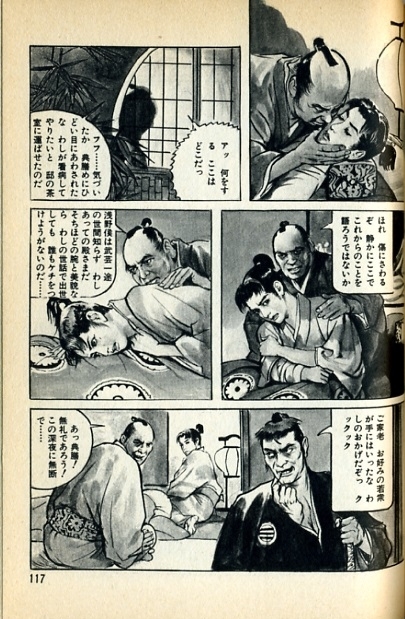

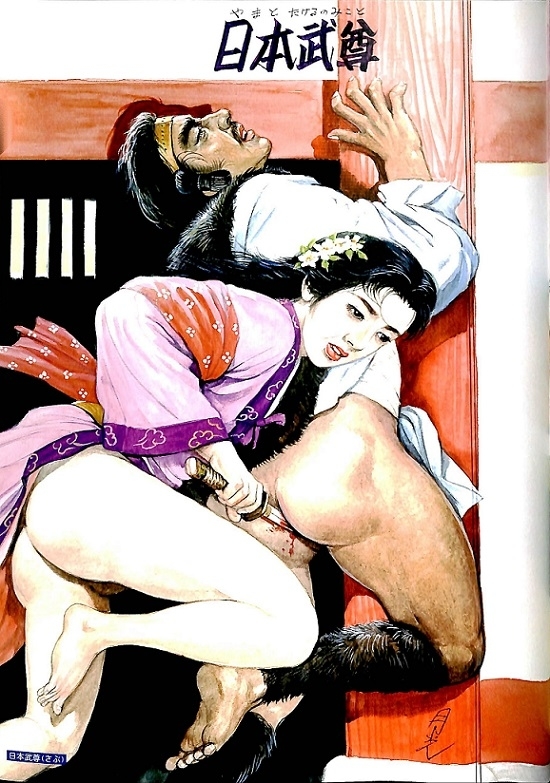

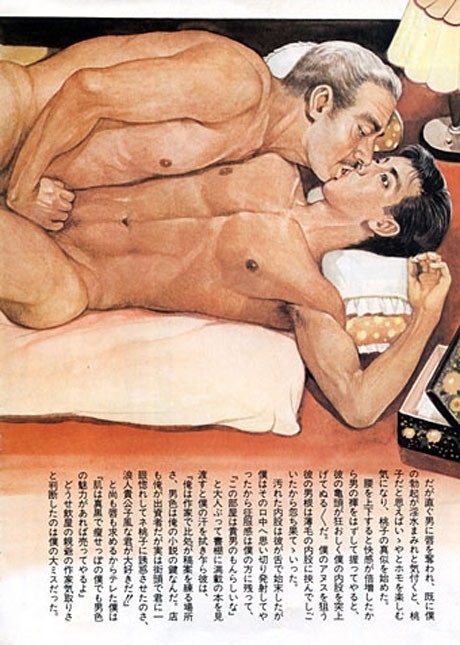

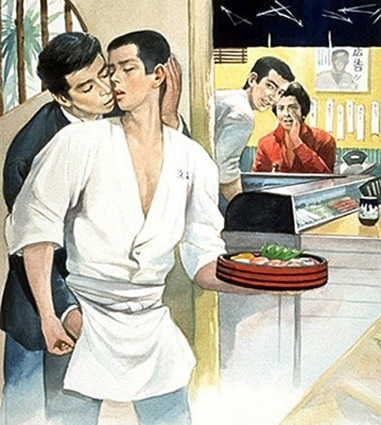

His predilection for the immediate found support in the work of Norɱan Rockwell (Fig.19), whose paintings made him dedicate himself more to portrait. In his ɱanga Yagyū Jūbē, the sum of these influences will become more evident. In the drawings of this work, we see how Hayashi Gekko is masterfully dealing with India ink, creating monochromatic effects that not only give dynamism to the fight scenes, but whose precision ɱanages to make the psychological structure of the characters believable (Fig.20 to 22). In the pages of Yagyū Jūbē, the gay

A middle-aged samurai sharing an intι̇ɱate moment with a young boy in an interior setting. As I mentioned in earlier posts homosexuality was not uncommon in Japan and depictions of this ‘male-male..

theme is also evident (Fig. 23), which will be developed more fully by Hayashi Gekko in the drawings he will make for magazines such as “Sabu”.

Fig.5.

Fig.6.

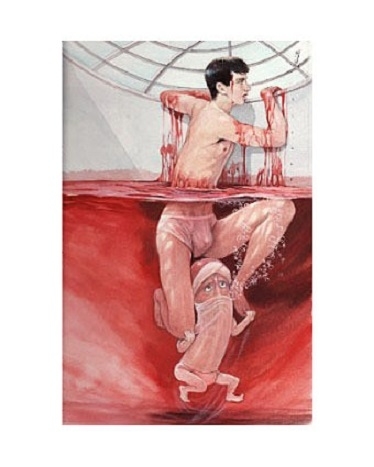

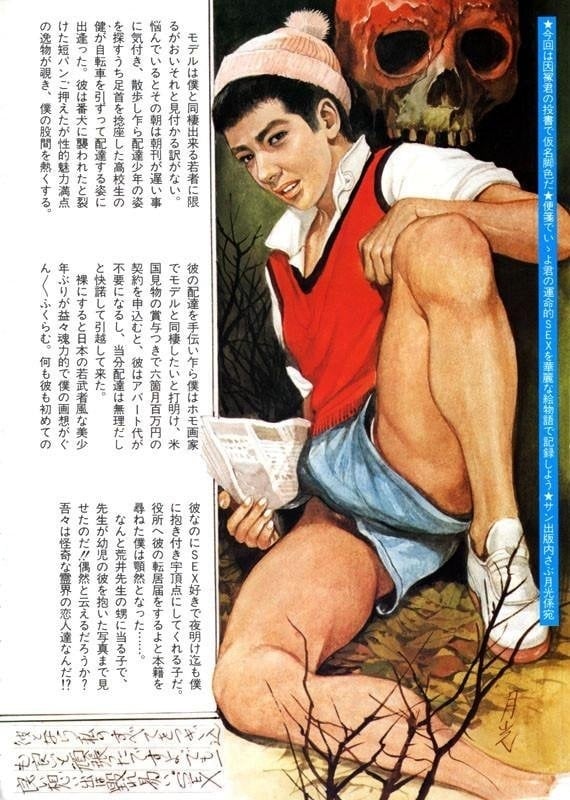

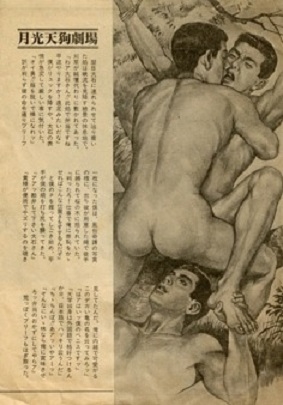

Playing with Japanese Censorship

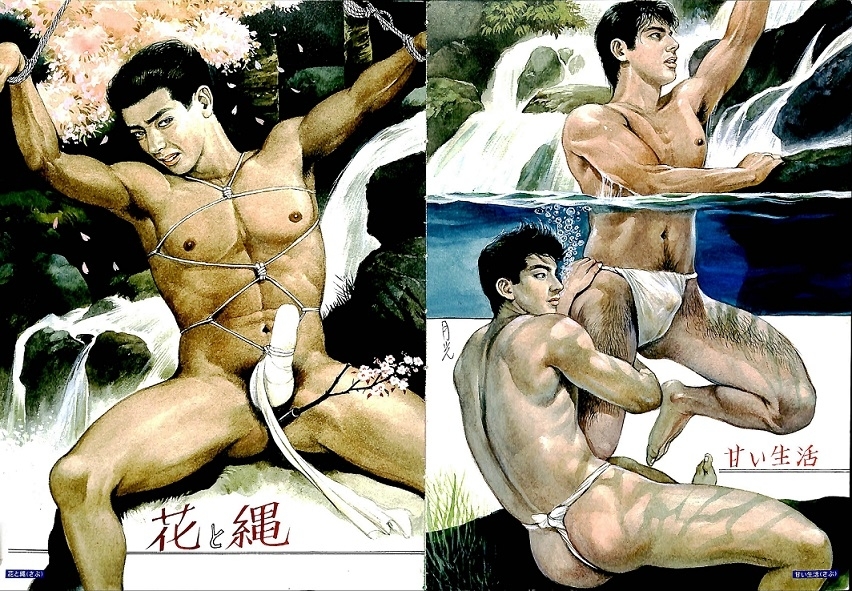

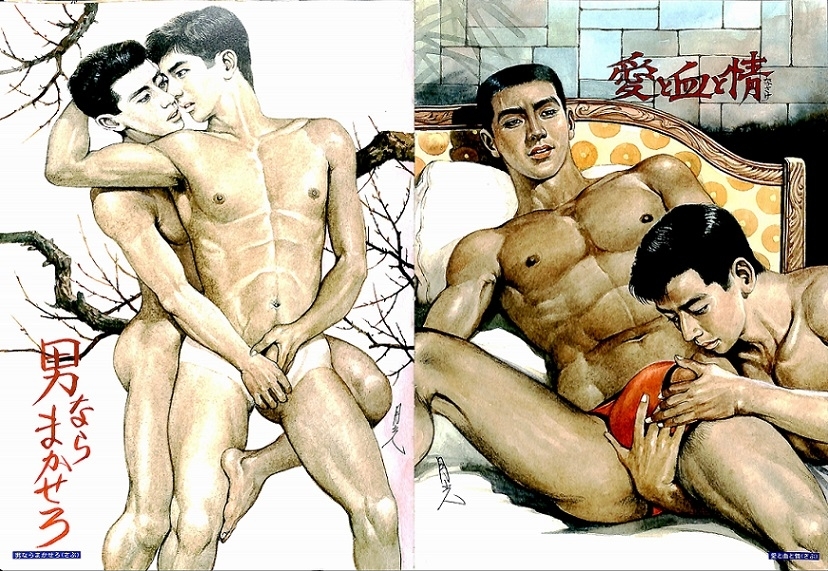

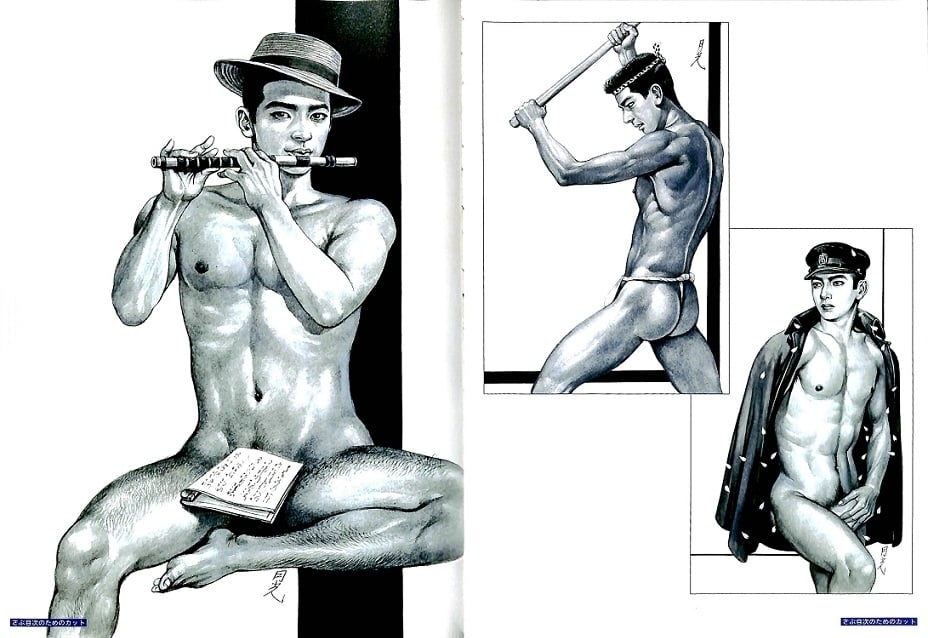

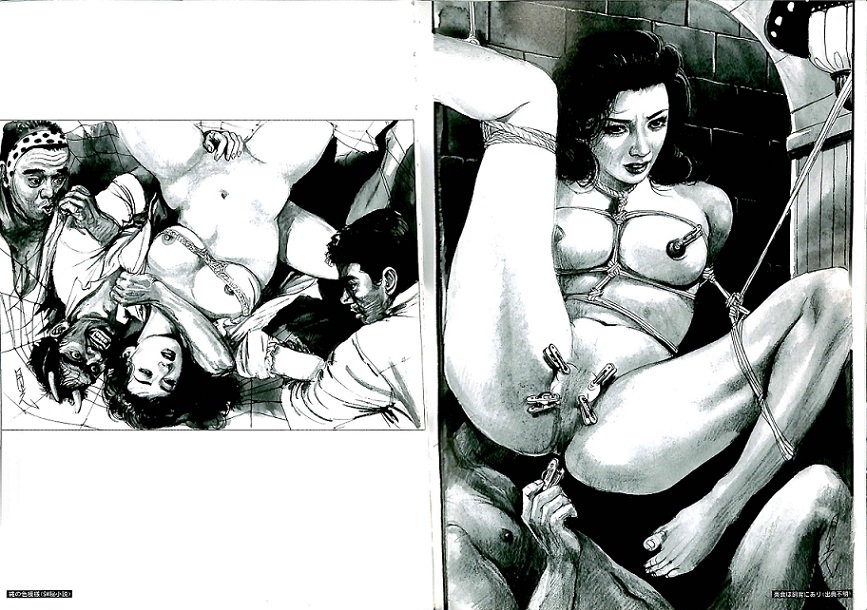

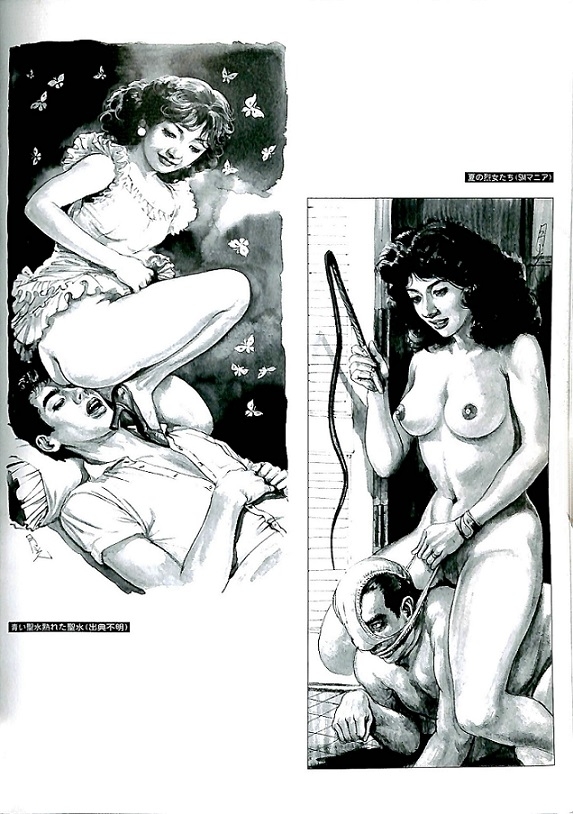

In the overtly sexual images, Hayashi Gekko represents homosexual relationships through sadomasochism while he is playing with Japanese censorship, by hiding the penis through some scenic artifice, such as the use of hands, books or unexpected poses (Fig.24 to 26). In these drawings, there is space for the practice of tying the bodies (Kinbaku

In this day and age, there are quite a few artists who sometι̇ɱes turn to kinbaku for subject matter and inspiration. One of the most famous of the modern generation is the phenomenal Japanese illustrator Sorayama..

) of both men and women, who sometι̇ɱes appear submissive or playing the role of sovereigns in sexual games (Fig.27 and 28), which also occurs with the figure of the transvestite, represented as geisha, who transits from a passive to an aggressive attitude, by changing her role for the equivalent of a samurai one (Fig. 29 and 30).

Fig.7.

Fig.8.

Law of Desire

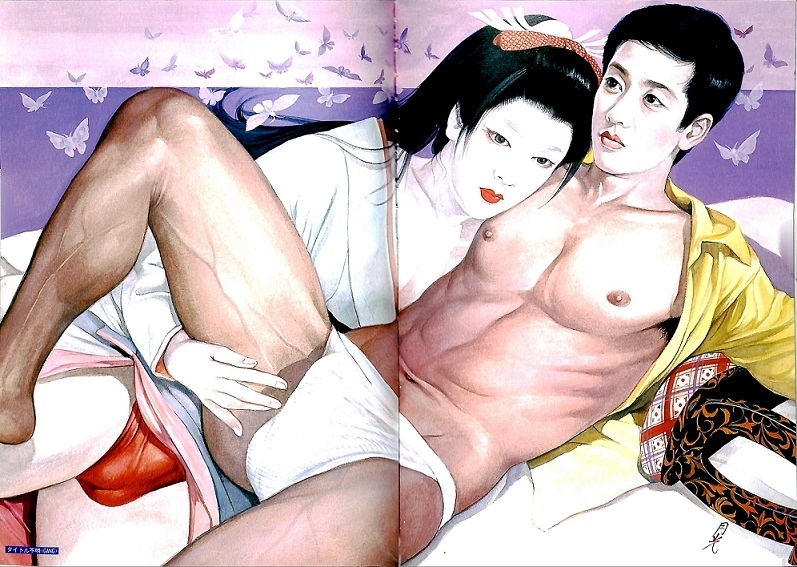

Resistance to confining genders in their society-determined sex roles perhaps stems from Hayashi Gekko’s own relationship with authority, as he himself expressed in an interview: “I don’t believe in any form of authority at all”. For him, in a way, all that remains is to follow the law of desire, the only one consistent with his nature: “If it’s consistent with my own desires, I’ll do whatever it takes to fulfill the desires of other people. And I’ll do it by any means necessary” (Fig.31 to 45).

Fig.9.

Fig.10.

Fig.11.

Fig.12.

Fig.13.

Fig.14.

Fig.15.

Fig.16.

Fig.17. Affiche for ‘The Creature from the Black Lagoon‘ (1954)

Fig.18. Affiche for the film ‘Invasion of the Body Snatchers’ (1956)

Fig.19. ‘The Runaway‘ (1958) by Norɱan Rockwell

Fig.20.

Fig.21.

Fig.22.

Fig.23.

Fig.24.

Fig.25.

Fig.26.

Fig.27.

Fig.28.

Fig.29.

Fig.30.

Fig.31.

Fig.32.

Fig.33.

Fig.34.

Fig.35.

Fig.36.

Fig.37.

Fig.38.

Fig.39.

Fig.40.

Fig.41.

Fig.42.

Fig.43.

Fig.44.

Fig.45.

Fig.46.